Cultists and Hippies and Quacks, Oh My! Name-Calling in Anti-Organic Articles

- Anneliese Abbott

- Jun 12, 2025

- 3 min read

When I was teaching an introductory writing class at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one lecture was devoted to discussing logical fallacies. One of the first fallacies we always talked about was the ad hominem attack – pointing out something unsavory about a person and using it to discredit their ideas. That’s a logical fallacy because even bad people can have logical ideas. And, of course, not all ad hominem attacks are true.

Most of the scientists who wrote articles opposing organic farming in the 1970s fell into the trap of using ad hominem attacks. This usually took the form of name-calling, sometimes paired with personal attacks against J.I. Rodale or other organic leaders. In one reference document in J.I. Rodale’s papers, he compiled a non-comprehensive list of some of the names organic farmers had been called. These included nuts, crackpots, Communists, McCarthyites, food faddists, “purveyors of so-called health foods,” “writers of ‘sensation’ articles,” irresponsible quacks, “a misguided but militant minority,” “flustered old ladies,” “misinformed or irresponsible people,” and “‘scare’ pamphleteers.”

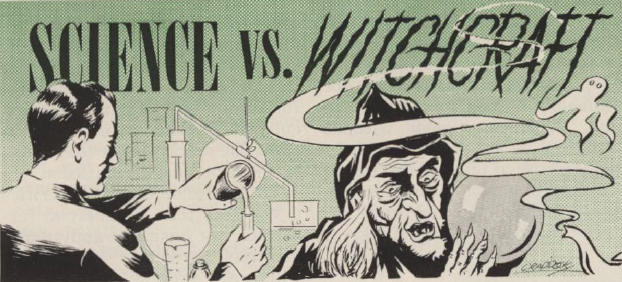

This type of name-calling started back in the late 1940s. In 1947, Rutgers University soil scientist Firman Bear called organic farmers “cultists.” By the end of that year, the list of names had grown to include witches, charlatans, and mystics, with the dark hint that they were inclined to “fall back on the supernatural when pressed by the scientist.” “There is more than a superficial resemblance between the attitudes of the organic cultists and those of the witch doctor,” Russell Coleman, president of the National Fertilizer Association, said in 1951. The industry magazine Fertilizer Review gleefully reprinted his quote in an article titled “Science vs. Witchcraft.”

Ray Throckmorton, dean of agriculture at Kansas State College, called organic farmers a “cult of misguided people” who “would—if they could—destroy the chemical fertilizer industry on which so much of our agriculture depends.” His article “The Organic Farming Myth,” published in Country Gentleman magazine in 1951, was accompanied with a cartoon of a barker at a carnival sideshow urging the audience to “try our miracle mixture (guaranteed non-scientific).”

By the 1970s, calling organic farmers cultists or quacks was standard practice in the barrage of anti-organic articles put out by agricultural and nutritional scientists. This time, though, they added on a new type of ad hominem attack. Organic gardeners weren’t just old ladies in tennis shoes anymore. Now they were the much-despised hippies, young people who broke with all sorts of established norms to make their own alternative lifestyle. “Being untrained and unskilled in the basics of plant growth, they have an almost mystic reverence for nature and a fear of man-made chemicals,” World Agriculture magazine warned in a 1978 article. “Their concerns are reinforced by highly selective reading and acceptance of anti-chemical literature to the exclusion of more scientific and better balanced reports.”

What did these attacks do to disprove organic farming? Nothing. Even if organic farmers were cultists, quacks, charlatans, witches, or hippies, that didn’t automatically make their ideas wrong. Weird people can sometimes have valid ideas, and “normal” people like white-coated scientists can sometimes believe things that just plain aren’t true. A truly logical investigation of organic farming would focus strictly on the ideas, not on the eccentricities (real or imagined) of the people who came up with them.

Comments